I was 42 when the American Airlines aircraft I'd boarded in Chicago was set to explode in midair.

Beneath me, in the baggage hold, was a live bomb shipped by Theodore Kaczynski, a.k.a. the Unabomber. As we headed toward Washington, D. C., his device ignited a powerful mix of explosive chemicals that somehow failed to incinerate me and 77 others on the plane.

This was November 15, 1979. Miraculous—or lucky—as our survival was, I have never thought of it as the defining event of my life; in fact, I've thought of it surprisingly little as other issues have occupied me over the decades. But now as every day brings ghastly news of bomb casualties—of so many unfolding lives blasted into the void—the heft of my own, still-flowering life feels almost unnatural.

I had everything to live for the day I boarded Flight 444 and sat unknowingly above the bomb. My two daughters were just pre-teens; my career as an editor and journalist was flourishing. I'd left a troubled life in New York for a fresh start in Chicago. Divorced, I was enjoying new relationships, developing enlightened attitudes for a second-time-around.

Meanwhile, Kaczynski was a man who, midway through life's journey, had entered a dark forest and lost his way out. From Chicago and then a cramped cabin in Montana, he was scheming to avenge the perceived evils of technology through symbolic maimings and killings. Before he was captured in 1996, his mail bombs would murder three and injure some 28.

Early on, he sought to make an emphatic statement by exploding an airliner in mid-flight. He fashioned a bomb out of batteries, a barometer, and enough incendiary chemicals to convert me and my fellow passengers into a tropospheric ball of fire. He packed the bomb in a wooden box, which he then shipped airmail from a Chicago suburb.

It ended up as postal baggage on our flight out of O'Hare. We were bound for Washington National Airport (now Reagan National Airport). According to FBI reports, Kaczynski's home-made altimeter cued the ignition device at 34,500 feet. We should have all died.

His device ignited all right. We heard a thud; acrid smoke streamed from below and choked the cabin. No one knew what had happened, but we were told to don the released oxygen masks and assume crash positions while the pilots raced for Washington's Dulles Airport, some 25 minutes away.

Those minutes went by in uncanny silence. With heads nested in folded arms, passengers seemed to be forestalling catastrophe by force of stillness, willing the plane to safety before smoke asphyxiated us or flames reached the fuel tanks. But no doubt the silent thoughts were as varied as the passengers' makeups. Prayers. Anguish. Terror. In my own mind, a soul-sickening flash of mortality shaped itself into a dark mantra: This is the unspeakable thing that can't be happening, that happens only to others, that we believe will not happen to us—but here it is happening. It IS happening. I uttered "agnostic-in-a-foxhole" prayers. I thought of my children.

We made it to Dulles—with an abrupt landing that rocketed unfixed objects toward the front. I scrambled through the plane's rear exit and ran with other passengers along the runway past ambulances and fire trucks, ran with the giddiness of being alive. It still only happens to others. It doesn't happen to me!

The resonance of mortal fear, the introspection that might have come from a few quiet days was dispelled by journalistic duties and impulses: Get pictures of the plane and people being treated for smoke inhalation; call in a news tip; get yourself to the convention you're here to cover...

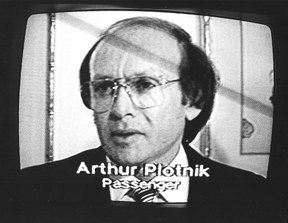

My giddiness carried over to a brief interview that afternoon on Washington's NBC-TV, which fed my talking head to the national evening news. "Scary," I said, giggling.

Seasons passed before I learned that the muted fire, far from arising from some accidental cause, was connected to the Unabomber. Years went by before smaller details were unveiled: How Kaczynski's package bore a Frederick Douglass stamp and one captioned, "America's light fueled by truth and reason." How he mewled over the cost of the bomb's materials; how he packed a 64-ounce juice can with pyrotechnic chemicals which seem to have burned, but—for reasons still unknown to me—failed to blow.

My life did flower. I worked with words, advanced the cause of libraries—a happy career. I wrote and still write with gratifying results. I've been joyously remarried for over a quarter century. My family enriches my life. My days are full.

But sometimes, when lives are snatched from the latest bomb victims, I'm prompted to seek meaning in my own escape from annihilation. Many of us survive close calls in this hazardous world. Is there a destiny or revelation at play? Are we special? What is it we've been saved to do?

I seek meaning, but come up short.

Survival doesn't anoint me as saint or world-saver. I don't feel chosen or special, or bound to some grand mission. That's TV stuff—or the delusions that sometimes drive unabombers and "martyrs" who blow up children. No, I'm satisfied to be honoring the miracle of life by moving through its luminescence as peacefully, cheerfully, and long as possible. Someone has to be there—people like you and me—to keep the light on. Whether we're enabled to do so by luck or providence, I don't know.

If any epiphany came out of my survival it was when my uncle, a droll California attorney, saw me on NBC that evening and reported, "You were good until you giggled." He had it backward. I was good when I giggled, for all the madmen to see.

Arthur Plotnik, formerly an editorial director at the American Library Association, is the author of eight books, including two Book-of-the-Month Club selections. His latest is Better than Great: A Plenitudinous Compendium of Wallopingly Fresh Superlatives (Viva Editions, 2011).