It’s simulation day at Atlanta’s new Maynard H. Jackson Jr. International Terminal. Fifteen hundred people with nothing better to do have volunteered to come down and try it out two weeks before opening day.

We’ve each been given “scripts” telling where we’re supposed to “fly” and what we’re supposed to do in the new terminal: go to the duty free shops, find the SkyClub, locate the shuttle to Macon (“but don’t get on the shuttle!” the script cautions).

My sons are good sports, and agree to come along with me.

Jake (green-&-white stripes) has just finished his freshman year at Northeastern and has nothing better to do. Ben will miss a couple of his high school classes.

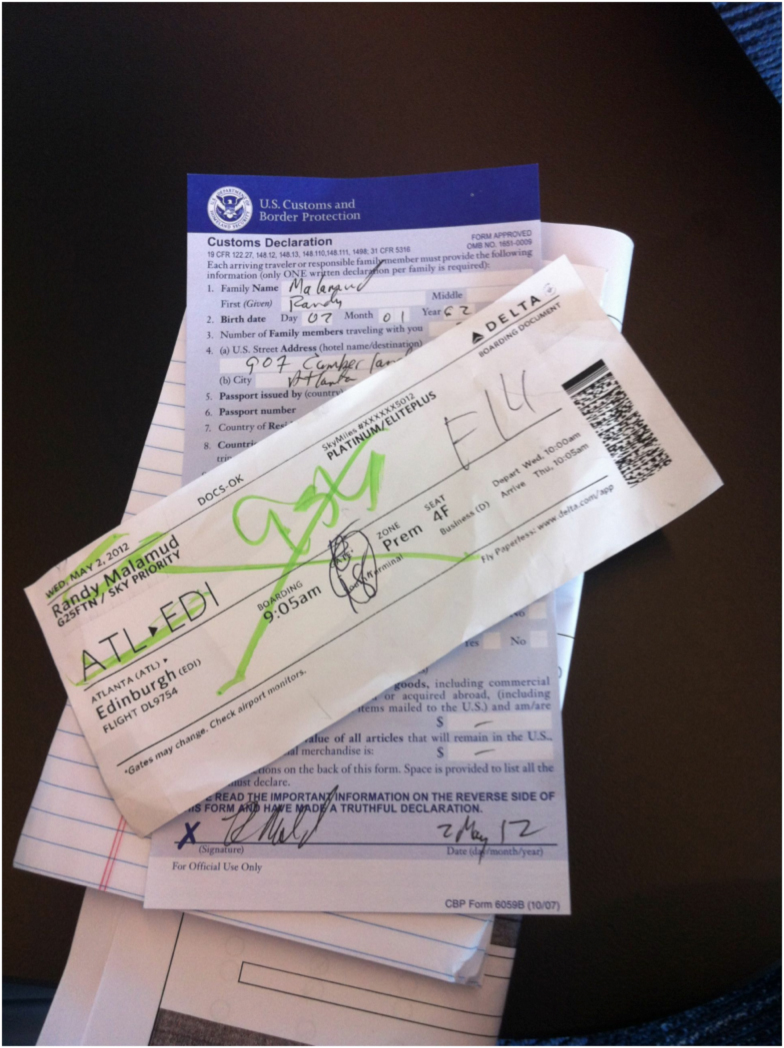

We check in (“Volunteers are asked to bring at least two old suitcases, golf bags, garment bags, etc. with old clothes or towels inside to process through the new baggage system”) for Delta flight “9754,” to “Edinburgh,” “leaving” at 10:00 and “arriving” at 10:05. At 10:15, we “return” to Atlanta, “arriving” at 10:30. Jake and I are ticketed in business, but Ben’s in coach, which annoys him because he’s actually a Silver Medallion and Jake’s not.

At the counter, I try to get Ben upgraded, and the agent checks to see if he can arrange this (“Maybe I can do it for a fee,” he says. “Dad, please don’t pay real money for this,” Ben whispers), but seems to forget about it before he has finished printing out our boarding passes. Here and elsewhere throughout the terminal, staff seem not quite sure how to handle the basics of check-in: no one can figure out exactly which gate our “flight” is supposed to leave from, for example. Good thing they’re doing a dry run.

The new terminal is...completely adequate. The approach from the highway is futuristic-brutalist, efficient, sterile.

The façade features the glass and curves you’d expect.

It’s not Schiphol or CDG or Eero Saarinen’s TWA terminal; it doesn’t aspire to be anything like those. It’s just a tiny bit snazzy, with a couple of funky chandeliers, but nothing that would even mildly jostle middlebrow sensibilities.

It’s like an entrée with one chili pepper at P.F. Chang’s.

The ceilings undulate, as ceilings tend to do nowadays.

Inexplicably, the carpet pattern seems to be a parody of a seascape, with neurotically exaggerated waves.

The carpet tiles don’t line up with each other, not even close. The bad visuals amplify the noxious new carpet smell to create a generally nauseating effect.

The most appealing aspect of this terminal is that passengers are surrounded by runways in every direction, a prime attraction of any terminal—and, of course, something that’s pretty hard to mess up in an airport design. There’s a great view of my favorite Hartsfield icon: “FLY DELTA JETS.” It’s really the single colorful feature in ATL, the only thing in this massive compound that has any personality. When I see it, I know I’m home. (How long has it been since people called airplanes “jets”?)

Ben points out that the volunteers’ demographics are surprisingly varied: “You’d think it would be all retired people.” But there are old and young volunteers here, men and women, kids, toddlers. There’s a woman in a powered wheelchair, apparently on her own, who seems to have considerable difficulty getting around—it surprises me that she signed up for what must be a difficult outing when she didn’t actually have to go anywhere.

Which raises the question of why any of us are here. Most of us seem to be wondering that about all the others. Perhaps part of our motivation is public service: helping to get the bugs out of the system. Also, self-interest: learning how to navigate the new terminal in advance. The airline and airport employees seem very grateful to have us here; they bestow on everyone the gushing warmth that’s usually reserved only for first-class passengers.

It’s a little bit surreal seeing hundreds of “passengers” sitting around waiting for their “flights.” There’s the air of tedious impatience that always pervades waiting rooms, but obviously we’ve all asked to come here and wait, knowing that we wouldn’t really be waiting for anything. So we can’t complain.

We get to our gate and “board”—which means standing in the jetway for about 10 minutes. After that, we’re arriving passengers, and we file through to the customs and immigration hall. The lines there are long, and by this point most of the crowd, like us, seems to be over the novelty of it all.

The immigration officers are completely incompetent, even though they’re not really processing arriving passengers. I don’t know if they’re pretending to be incompetent just to make this simulation seem realistic, or (more likely) that incompetence is simply their quidditas. It takes us an extra 15 minutes here, because Jake’s a smart-ass. As we’re standing at the counter, a propos to nothing, he blurts out: “We brought back lots of agricultural diseases from Edinburgh.” The officer looks up slowly, thinks about it for a couple of minutes, and calls over a supervisor. “How do you refer somebody,” he asks? It takes him a while to figure it out (for future reference: type in “R”), and we get referred, and then another agent walks us through the hall, and checks and clears us. Our trip to nowhere ends a bit anti-climactically.

For those of us who spent the morning wandering around the airport without going anywhere, the simulation highlighted the aspects of airport transit that are pure routine and drudgery. Yet part of what’s so compelling about this drudgery, paradoxically, is how intrinsically connected it is with the astounding phenomenon of flight and the fascination of travel. The dull bits provide a necessary counterpoint to all that: we enjoy the soaring adventure all the more because of the contrast with the security line farce and the brutal skirmish to find outlets for recharging smartphones.

I love airports—I love moving through them and luxuriating in the mechanics of mobility. It’s more fun, obviously, when I’m really going somewhere, but this pretend trip gave me the chance to think about what part of the experience comes simply from being at the airport. It’s not a lot, but it’s also not nothing. An ok time was had by all.

Randy Malamud is chair of the English department at Georgia State University in Atlanta. His most recent book, forthcoming this summer, is An Introduction to Animals and Visual Culture (Palgrave Macmillan) and he's working on a new project about travel tentatively called The Globalist Humanist Tourist: The Importance of Elsewhere.